There's no escaping the recent decision by the Supreme Court of the United States legalizing homosexual marriage across their country. The media and the internet are saturated with coverage. Even Facebook has gotten into the act with people overlying their profile photos with rainbow flags. The number of people in the West who support heterosexual-only marriage continues to shrink rapidly and the issue becomes more of a liability for politicians than anything else. The question I wish to ask today is: what does it matter to us Jews?

On the surface of it, not much. The average homosexual, like the average heterosexual, isn't a rampaging crusader but rather just wants to lead a normal, quiet life. Attendance at gay marriages is still optional, not compulsory. Let them do their thing and leave us alone to do ours.

However, the threat to Judaism in the West isn't from the average heterosexual. In all other ethnic, religious and cultural communities there is a minority which can't stand the idea that their views are not the standard views across society.

The homosexual community is no different. That the state permits gay marriage isn't enough for this group. The idea that there are other communities out there that dispute the "enlightened" ruling of the court and continue to believe it's forbidden is intolerable to them. These are the people who look specifically for religious bakers and sue them in human right's court when they are refused a wedding cake. For these people the ruling will not simply be about getting married. They are in a state of cultural war with traditional religion because traditional religion opposes their important values and they can't tolerate that.

Look at it a different way. In more savage parts of the world culture wars are conducted at the business end of an automatic rifle. ISIL uses its military might to enforce it's version of Islamic law on its conquered subjects. You can be sure that prohibiting gay marriage is part of that cachet. In the West we don't fight that way. Instead of rifles we have lawyers and instead of tanks we have judges. The culture war is fought in a more civilized, genteel fashion, but the end result is the same: the winning side seeks to impose its values on the losing side and goes apoplectic when it fails.

The reason we need to care is because of this militant minority. There have already been cases where businesses being run by religious Chrisians have been targeted and legally attacked for refusing service to a gay couple seeking to get married. On one hand you can sympathize with the gay couple. After all, if you read a story in the paper about a Black man being denied entry into a restaurant because the management only wanted White customers you'd be justifiably outraged. On that level this is no different.

On the other hand, consider that in the cases involving gay couples the businesses made efforts to assist the couple by recommended alternative companies that would offer the same product at the same or an even better price. The response by the couples was uniform: We don't just want a cake. We want you to bake that cake. Why? If I went into a store and got the strong impression my patronage was not wanted because I'm Jewish I would take my money and recommendations elsewhere. I wouldn't double-down and insist that this business serve me. Why would I want them to benefit in any way? These couples did the opposite - they chose to punish the religious individuals financially and legally.

Small time, sure, but what happens one day when a gay couple walks into the local Orthodox shul and demands to rent the social hall for their wedding? What happens when a gay groom demands an aufruf?

Assaults on religious freedom have been protected by law until now because of the idea of freedom of conscience. Read the media now and the liberal lobby is already re-framing that argument. It's no longer about freedom of religion but about freedom from discrimination. You wouldn't tolerate an institution that forbid interracial dating so you soon won't have to tolerate a shul or church that forbids homosexual marriage. Imagine the day when someone looks at an Orthodox Jew applying for a job and says "We don't want people who don't support gay marriage working here".

Seen that way we as Torah-observant Jews might be a more precarious position than we think.

The ongoing ramblings of the Leader of the Living and his thoughts on Judaism, Israel and politics today. Contact me at GARNELIRONHEART@OUTLOOK.COM

Tuesday, 30 June 2015

Sunday, 28 June 2015

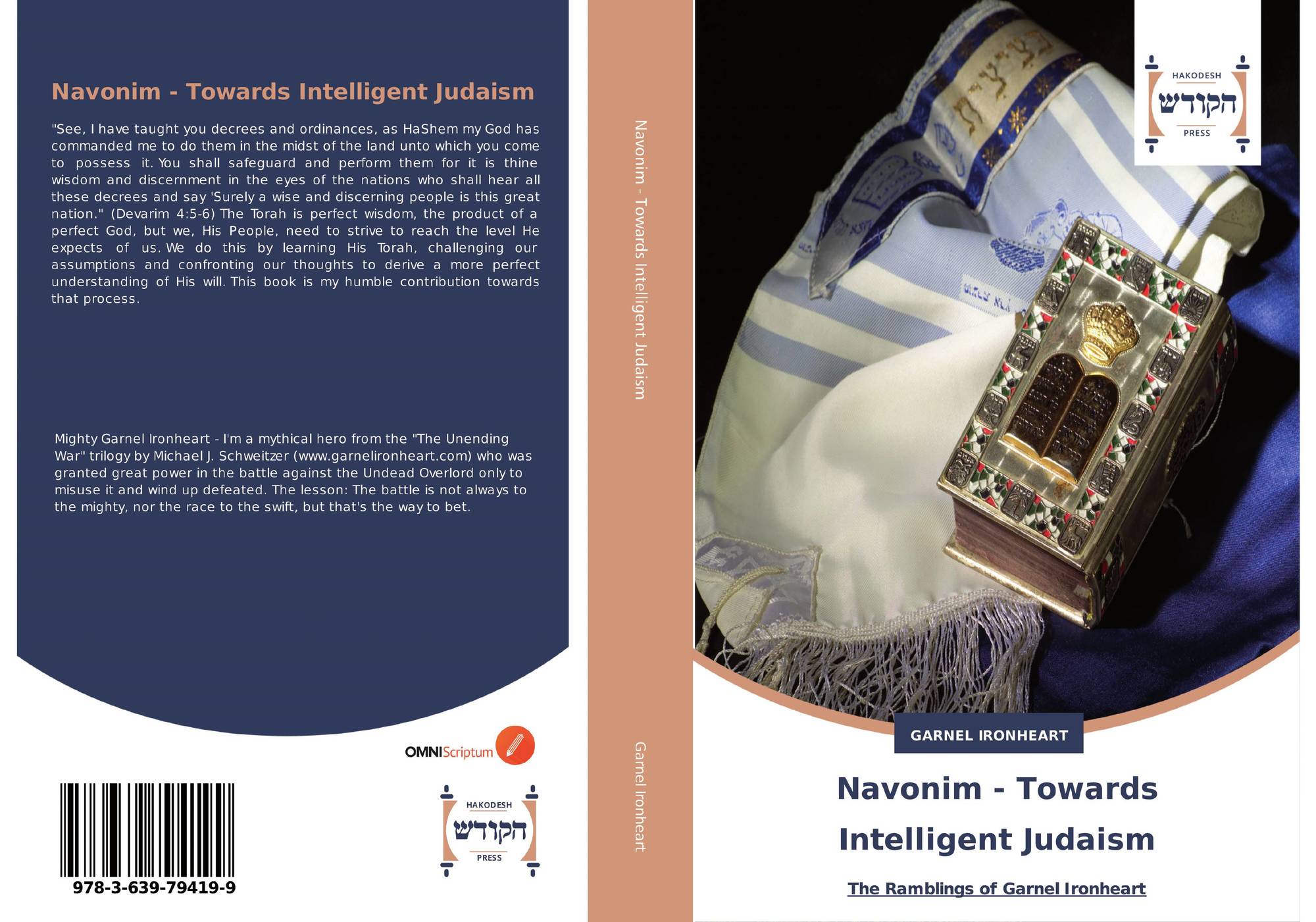

Garnel Ironheart - The Book!

|

First, there was the book that brought me into existence, The Curse of Garnel Ironheart. Then, after the conclusion of the three books of The Unending War trilogy there was the establishment of this blog which allowed me to share my thoughts with the world. And now, as the next logical step in my process towards Jewish world domination, comes Navonim - Towards Intelligent Judaism, a collection of the finest essays on my Jewish ideology, Judaism and Jewish politics and thoughts on many parshiyos of the Torah.

One of the main reasons for my starting and maintaining this blog was and is to add my voice to the cacophony inundating the Jewish world today. I certainly hoped I'd have more of an impact than I did but still feel great about all the views I could share and the occasional discussions that those views engendered.

So when I was recently contacted by Hadassa Word Press (the same company that contacted pretty much every Jewish blog they could find, I think) and asked if I'd be interested in publishing a book based on my blog posts I decided to take advantage and submitted a manuscript.

Navonim - Towards Intelligent Judaism consists of many of the posts I wrote on my Navon ideology along with my thoughts on Orthodoxy today and, as mentioned, some Torah thoughts in the third section. It's a fine collection of essays sure to give the dedicated reader hours of enjoyment and insight.

At this time it's only available directly from Hadassa Word Press either as a download or as a pricey bound edition which will enhance the appearance of your book shelf and excite the comments of your friends and neighbours. While you're there, pick up more copies of the books of The Unending War trilogy, the story that brought me to life! However, if you wait I am told that it will eventually appear on Amazon as well.

And who knows? If enough people buy the book, or should I say: sefer, and notoriety develops perhaps I too will merit to have it burned at Meron on Lag B'Omer.

So when I was recently contacted by Hadassa Word Press (the same company that contacted pretty much every Jewish blog they could find, I think) and asked if I'd be interested in publishing a book based on my blog posts I decided to take advantage and submitted a manuscript.

Navonim - Towards Intelligent Judaism consists of many of the posts I wrote on my Navon ideology along with my thoughts on Orthodoxy today and, as mentioned, some Torah thoughts in the third section. It's a fine collection of essays sure to give the dedicated reader hours of enjoyment and insight.

At this time it's only available directly from Hadassa Word Press either as a download or as a pricey bound edition which will enhance the appearance of your book shelf and excite the comments of your friends and neighbours. While you're there, pick up more copies of the books of The Unending War trilogy, the story that brought me to life! However, if you wait I am told that it will eventually appear on Amazon as well.

And who knows? If enough people buy the book, or should I say: sefer, and notoriety develops perhaps I too will merit to have it burned at Meron on Lag B'Omer.

Friday, 26 June 2015

An Accessory To Mitzvos

There's been a terrible tragedy in the community I live in. A week ago during a party a 6 year old girl slipped under the surface of the swimming pool she was in and laid at the bottom for several minutes (no one really knows) until she was discovered. She was hauled out of the water, had CPR done and was immediately taken by ambulance to the local emergency room. From there she was transported to the nearest Pediatric ICU, the one in my town. She is still there, intubated and ventilated with no improvement over time. Investigations have shown that her brain and brainstem are completely gone. No change is expected. Tragedy.

The parents are in a difficult spot. Their position on the Jewish definition of death is absence of heart beat. Therefore as far as they are concerned their daughter is alive. What's more, they see themselves as being machmir in having decided that if this little girl's heart should stop beating they want all resuscitative efforts to be made to restart it. The hospital staff, approaching this from a secular ethics perspective have decided that she's dead and that taking her off the ventilator would be acceptable. All they need is the parents' permission which, naturally, they're not getting.

So I went one evening to visit the family and offer them a refuah sheleimah even though my heart wasn't into it. I mean, yes there is God in Heaven and He can perform whatever miracles He wants unhindered but we don't walk around on a daily basis assuming that those will happen simply because we need one or prayed really hard for it. The patient has unfixable brain damage. According to the brainstem position in halacha she's already dead. I wished them a refuah sheleimah and hoped we'd see nissim v'nifla'ot but in my head I knew those weren't likely to happen.

It's the reaction to this tragedy that has me shaking my head though. The parents belong to a sect of Judaism that loves to do kiruv. In fact, other than other chasidim and stricter members of the Yeshivish community they even see other frum Jews as targets. Kiruv is their life, what they were trained to do since they were kids and what they see as the highest activity in their day. They constantly run campaigns to get women involved in Shabbos candle lighting and going to the mikveh. Important thigns.

It still bothered me to see lots of piles of pamphlets piled around the waiting room where people had gathered to comfort the family. The pamphlets detailed various mitzvos like lighting Shabbos candles and mikveh. Two women related to the family made it clear that they expected people to take on various mitzvos with the kavannah that it should help convince God to bring the girl a speedy recovery. In other words, this was another mitzvos campaign.

I tried to be understanding. In their mind the mishnah in Avos, the one right at the beginning about being servants of God without expecting a reward, probably doesn't apply here. Or perhaps there's a statement or two in that book they're always talking about, the one the first Rebbe of their movement wrote which they consider more important that any other Jewish book except (maybe) the Chumash. Fine, I get it. We do mitzvos and with the kavannah that the girl gets a refu'ah from Heaven. Any parent desperate for their child to recovery would grab at something like this. Who can blame them when the alternative is heartbreak for the rest of their lives?

What bugged me though was listening to the parents talk about this mitzvah campaign. For them it isn't a maybe. It's not that they're saying that they'll give it their beset shot and what happens, happens. They fully expect that if enough people go to the mikveh or put on tefillin because of their efforts God will upend the natural laws of the world He established and ensures run with inviolability and heal this girl's dead brain. And the girl? She gets to lie in an ICU bed with a tube in her throat until that happens. She gets to stop being a person and instead gets to be a symbol, an accessory to the latest mitzvah campaign and an opportunity to hand out pamphlets and push the group's agenda. Should I be bothered that this will happen to her?

The parents are in a difficult spot. Their position on the Jewish definition of death is absence of heart beat. Therefore as far as they are concerned their daughter is alive. What's more, they see themselves as being machmir in having decided that if this little girl's heart should stop beating they want all resuscitative efforts to be made to restart it. The hospital staff, approaching this from a secular ethics perspective have decided that she's dead and that taking her off the ventilator would be acceptable. All they need is the parents' permission which, naturally, they're not getting.

So I went one evening to visit the family and offer them a refuah sheleimah even though my heart wasn't into it. I mean, yes there is God in Heaven and He can perform whatever miracles He wants unhindered but we don't walk around on a daily basis assuming that those will happen simply because we need one or prayed really hard for it. The patient has unfixable brain damage. According to the brainstem position in halacha she's already dead. I wished them a refuah sheleimah and hoped we'd see nissim v'nifla'ot but in my head I knew those weren't likely to happen.

It's the reaction to this tragedy that has me shaking my head though. The parents belong to a sect of Judaism that loves to do kiruv. In fact, other than other chasidim and stricter members of the Yeshivish community they even see other frum Jews as targets. Kiruv is their life, what they were trained to do since they were kids and what they see as the highest activity in their day. They constantly run campaigns to get women involved in Shabbos candle lighting and going to the mikveh. Important thigns.

It still bothered me to see lots of piles of pamphlets piled around the waiting room where people had gathered to comfort the family. The pamphlets detailed various mitzvos like lighting Shabbos candles and mikveh. Two women related to the family made it clear that they expected people to take on various mitzvos with the kavannah that it should help convince God to bring the girl a speedy recovery. In other words, this was another mitzvos campaign.

I tried to be understanding. In their mind the mishnah in Avos, the one right at the beginning about being servants of God without expecting a reward, probably doesn't apply here. Or perhaps there's a statement or two in that book they're always talking about, the one the first Rebbe of their movement wrote which they consider more important that any other Jewish book except (maybe) the Chumash. Fine, I get it. We do mitzvos and with the kavannah that the girl gets a refu'ah from Heaven. Any parent desperate for their child to recovery would grab at something like this. Who can blame them when the alternative is heartbreak for the rest of their lives?

What bugged me though was listening to the parents talk about this mitzvah campaign. For them it isn't a maybe. It's not that they're saying that they'll give it their beset shot and what happens, happens. They fully expect that if enough people go to the mikveh or put on tefillin because of their efforts God will upend the natural laws of the world He established and ensures run with inviolability and heal this girl's dead brain. And the girl? She gets to lie in an ICU bed with a tube in her throat until that happens. She gets to stop being a person and instead gets to be a symbol, an accessory to the latest mitzvah campaign and an opportunity to hand out pamphlets and push the group's agenda. Should I be bothered that this will happen to her?

Wednesday, 24 June 2015

Book Review: The Challenge of Jewish History

Rav Hool starts off by pointing that out traditional Jewish history and secular standard history contradict each other on a very important fact: how long did the Second Temple stand for? According to Seder Olam and various mephorshim it was around for 420 years. According to accepted secular history it was almost 600 years in standing. Which is correct?

I began reading the book with a cynical eye. After all, there is no shortage of books written by well-meaning rabbonim who try to disprove standard history or science in order to "preserve" the truth of a statement in the Talmud or Bible that conflicts with known facts. (cf. the famous Talmudic mud mouse) These books inevitably start by claiming that there is an obligation to believe the literal meaning of everything Chazal said, not just in halacha which is obvious, but in science, geography and other secular areas. Thus if modern science contradicts a Talmudic scientific statement then modern science must be wrong. All that's left is to present a highly selective assortment of statements by Chazal to prove that they were right.

This book is nothing like that. Rav Hool starts out by demonstrating all the evidence for the standard secular historical version. He then points out the inconsistencies or flaws in the historical record that are recognized by archaeologists and historians. His conclusion is the secular historical version of a 600 year Temple is workable and if it wasn't for our sources saying it was only 420 years he'd have no problem with it.

He then brings in the Jewish view on that history. His only references to the Bible or Talmudic-era sources are direct quotations from verses and chapters containing numbers of years in various areas. The assumption, naturally, is that these numbers are correct just as the assumption regarding the secular information was. This leads him to prove that there is a need to reconcile.

The way he does it is brilliant. According to secular history the Babylonian Empire was conquered by the Persian and Median empires. Persia, in turn was conquered in its entirely by Alexander the Great. Subsequent to his death the empire split into four kingdoms with the Seleucid and Ptoelmaic ones being the most relevant to us since they took turns ruling over Israel.

According to Rav Hool's information there is a fundamental error in the narrative. Using recent archaeological discoveries he brings convincing evidence that Alexander did not conquer the entire Persian empire, just a big chuck of its northwest. As a result Persia continued on in parallel to the Greek empire and subsequent kingdoms. This has the result of contracting history and shaving 200 years neatly off the secular version, bringing it in line with the Jewish accounting.

Again, this is not a book of Chareidi apologetics. The data Rav Hool brings is from the current archaeological literature, not Jewish speculative sources which allows a greater sense of reliability.

Using this data Rav Hool is able to suggest who Achashveirosh was in Persian history along with other historical events that occurred to our ancestors at that time as well.

I heartily recommend this book for folks with an interest in Jewish history. Despite getting tedious at times (Rav Hool loves his details!) it makes for a very interesting read overall and a new appreciation for events in that far off time.

Monday, 22 June 2015

Restoring This World

For centuries we, the Jewish people, lived in homeless exile. As a result of being under the rule of other nations, even in our Land, we were denied the ability to observe large areas of Torah law. Two thirds of the Talmud, Kodoshim and Tahoros were out of the picture. Much of Zeriam was inapplicable to the majority of Jews, even in Israel. And with only limited judicial autonomy much of Nezikin was also just theoretical. It is no wonder, then, that over 1800 years Judaism developed an obsession with those few parts of the law that was still relevant to regular life.

Along with that focus came a new interest in the spiritual. From vague references in the Torah to mysterious stories in Nach and occasional descriptions in the Talmud the spiritual developed over the centuries, especially after the "discovery" of the Zohar and the writing of the Ari HaKadosh came to light. In the last few decades, the push by the spiritualist, especially with the new dominance of Chasidish thinking over the Chareidi community and the outreach efforts of Lubavitch, have led to its having effects on every day Jewish thinking.

What is this effect? Consider the standard Lubavitcher line: this world is an illusion. Imagine its implications.

One can understand why this issue is of great concern to Jewish thinkers. God is infinite but if He is where does that leave room for us in the universe since He already occupies every nook and cranny? One solution is that there is nothing else occupying that space because it's not real. The door to my office, my car, my cell phone, none of these truly exist in this philosophy but are mere covers for their true spiritual essences which are all that really matter.

What has such thinking done to us? It seems to have created a belief system in which this world is given no value at all. Well, why should it have value? It's not really there. Besides, if the only thing that matters is Olam Haba then anything that is of value for this world alone is also meaningless. The result is a culture in which there is an emphasis on the spiritual, on the purely bein adam l'Makom aspect of Judaism and a concomitant disdain for all other aspects of Judaism. That's why we see endless examples of frum Jews who are meticulous in their observance of kashrus and complete menuvalim in their business and interpersonal affairs.

The emphasis on the spiritual has also contributed to the great divide between the secular and observant segments of our nation. Secular Jews, for lack of a proper Torah education (or sadly, sometimes because of one!) are focused on the physical, on what they can see and feel. They aren't so much worried about Heaven but about making that next mortgage payment and ensuring their families are well cared for. They prize effort and achievement in this world. Imagine the rejection they feel from observant Jews who sniff at their accomplishments because it has nothing to do with Olam Haba. Imagine their disgust at Jewish leaders who work to ensure their followers remain in penury so as to minimize the temptations of this world in order to maximize their reward in the Next.

But it does not have to be this way.

As Rav Kook, ztk"l, taught, there is definite holiness in this world because God created it and it impossible for something that was produced by his supernal holiness to be void of its own inner kedushah. Yes, everything has its own spiritual component but God is not on deity of trickery. If there's a door post in front of me the physical component exists as surely as the spiritual one does and since it is one of His creations it has value.

This is where Religious Zionism needs to set up a counterweight to combat this galus-based philosophy. In the absence of a State, in a wandering life where the questions of dealing with life in this world in all its facts, economic, agricultural, military etc., are absent one does not have to ascrbie any value to This World. Having return to our Land these issues come up anew.

Modern Chareidism has dealt with this issue by retreating even deeper into the "only the spiritual matters" position. We are told that the Israeli army doesn't really protect Israel, the Chareidi community's Torah learning (and, oddly enough, only theirs) does. The Michtav MiEliyahu's radical position that all effort in This World is worthless and only a "going through the motions" because it's the spiritual realm where reality actually happens is waved about as the "authentic" Jewish position on these matters when it's really not.

Religious Zionism needs to point out that the reason God gave us the Torah in this world is because He wanted us to use it in this world. There is holiness in all that goes into building Israel. There is spiritual worth in all those activities which protect Jews and help them prosper. It is through this understanding that we can reach out to our religiously alienated brethren and show them that, despite their lack of proper Torah observance in many areas they are part and parcel of the Jewish nation and essential components to it. Their hopes and dreams have meaning and, if sublimated to Torah values, can be essential in pushing forward our progress through the Final Redemption.

There is, of course, danger in this approach. A two way bridge encourages traffic in both ways. Emphasizing material value could come at the expense of appreciating spiritual value and only with both as the primary emphasis in approach worship of the Creator does one truly fulfill the Torah imperative. However, the cost of not doing it is what we see today - the vast majority of Jews, including in Israel, bereft of any sense of purpose or feeling of meaning in being Jewish. Could this change not help bring them closer to our heritage?

Along with that focus came a new interest in the spiritual. From vague references in the Torah to mysterious stories in Nach and occasional descriptions in the Talmud the spiritual developed over the centuries, especially after the "discovery" of the Zohar and the writing of the Ari HaKadosh came to light. In the last few decades, the push by the spiritualist, especially with the new dominance of Chasidish thinking over the Chareidi community and the outreach efforts of Lubavitch, have led to its having effects on every day Jewish thinking.

What is this effect? Consider the standard Lubavitcher line: this world is an illusion. Imagine its implications.

One can understand why this issue is of great concern to Jewish thinkers. God is infinite but if He is where does that leave room for us in the universe since He already occupies every nook and cranny? One solution is that there is nothing else occupying that space because it's not real. The door to my office, my car, my cell phone, none of these truly exist in this philosophy but are mere covers for their true spiritual essences which are all that really matter.

What has such thinking done to us? It seems to have created a belief system in which this world is given no value at all. Well, why should it have value? It's not really there. Besides, if the only thing that matters is Olam Haba then anything that is of value for this world alone is also meaningless. The result is a culture in which there is an emphasis on the spiritual, on the purely bein adam l'Makom aspect of Judaism and a concomitant disdain for all other aspects of Judaism. That's why we see endless examples of frum Jews who are meticulous in their observance of kashrus and complete menuvalim in their business and interpersonal affairs.

The emphasis on the spiritual has also contributed to the great divide between the secular and observant segments of our nation. Secular Jews, for lack of a proper Torah education (or sadly, sometimes because of one!) are focused on the physical, on what they can see and feel. They aren't so much worried about Heaven but about making that next mortgage payment and ensuring their families are well cared for. They prize effort and achievement in this world. Imagine the rejection they feel from observant Jews who sniff at their accomplishments because it has nothing to do with Olam Haba. Imagine their disgust at Jewish leaders who work to ensure their followers remain in penury so as to minimize the temptations of this world in order to maximize their reward in the Next.

But it does not have to be this way.

As Rav Kook, ztk"l, taught, there is definite holiness in this world because God created it and it impossible for something that was produced by his supernal holiness to be void of its own inner kedushah. Yes, everything has its own spiritual component but God is not on deity of trickery. If there's a door post in front of me the physical component exists as surely as the spiritual one does and since it is one of His creations it has value.

This is where Religious Zionism needs to set up a counterweight to combat this galus-based philosophy. In the absence of a State, in a wandering life where the questions of dealing with life in this world in all its facts, economic, agricultural, military etc., are absent one does not have to ascrbie any value to This World. Having return to our Land these issues come up anew.

Modern Chareidism has dealt with this issue by retreating even deeper into the "only the spiritual matters" position. We are told that the Israeli army doesn't really protect Israel, the Chareidi community's Torah learning (and, oddly enough, only theirs) does. The Michtav MiEliyahu's radical position that all effort in This World is worthless and only a "going through the motions" because it's the spiritual realm where reality actually happens is waved about as the "authentic" Jewish position on these matters when it's really not.

Religious Zionism needs to point out that the reason God gave us the Torah in this world is because He wanted us to use it in this world. There is holiness in all that goes into building Israel. There is spiritual worth in all those activities which protect Jews and help them prosper. It is through this understanding that we can reach out to our religiously alienated brethren and show them that, despite their lack of proper Torah observance in many areas they are part and parcel of the Jewish nation and essential components to it. Their hopes and dreams have meaning and, if sublimated to Torah values, can be essential in pushing forward our progress through the Final Redemption.

There is, of course, danger in this approach. A two way bridge encourages traffic in both ways. Emphasizing material value could come at the expense of appreciating spiritual value and only with both as the primary emphasis in approach worship of the Creator does one truly fulfill the Torah imperative. However, the cost of not doing it is what we see today - the vast majority of Jews, including in Israel, bereft of any sense of purpose or feeling of meaning in being Jewish. Could this change not help bring them closer to our heritage?

Monday, 15 June 2015

Feminine Orthopraxy

I wonder if this is what it was like in the early days of the Reform movement in Germany. You know, a group of people get together and create a new sect, they proclaim their ideology and start to attract people and the establishment wonders how long it will be before this fringe community disappears. Except that it doesn't.

Are we witnessing a new sect in Judaism arising in our midst now? With the ongoing efforts of the Open Orthodox to pump out women rabbis and erase as much of the gender separation intrinsic to Judaism as they can without crossing certain red lines it's worth wondering if, ultimately they will become yet another "stream" in modern Jewish life, like the Reform, Conservatives, etc.

Some might wonder why I might describe them as a group separate from Orthodoxy? It's important to note, for example, that they do not advocate changes in Shabbos, kashrus, or taharas mishpachah, the three pillars of Jewish religious life. From their publicity photos we seen men and women dressed in appropriate head coverings and clothing. This isn't about women in tank tops and bare headed men shouting "We're traditional!" These are folks who keep the vast majority of the rules to the best of their ability except for one or two areas where they have decided that the lack of a definite prohibition in chumash has allowed them to innovate.

It's important to remember as well that during its heydey in the mid-20th century, the Conservative movement wasn't that far from modern Orthodoxy. In many Conservative synagogues the only non-Orthodox feature was the mixed seating, and we would do well to remember that at that time many Orthodox synagogues were experimenting with partial mixed seating (family seating I believe it was called), further blurring the differentiation.

The Conservative example is instructive in another way though. Yes, in 1950 the only difference between a Conservative synagogue and the Orthodox shul down the street might have been the seating arrangement but fast forward 50 years and suddenly those two buildings were now irreconcilably different. The Orthodox shul was still plugging along with the same old rituals and arrangements while the Conservative synagogue was fully egalitarian, pushing homosexual rights and emphasizing an ecofascist tikun olam over archaic rules such as not driving on Shabbos. It seems odd to think that the trigger for the ongoing deviation from Jewish norms towards secular liberalism with token ritual acts was the mixed seating but it's hard to derive another conclusion. Mixed seating, after all, represents the demand of the Jewish congregant to get something out of his service as a price of participation instead into of contributing to it altruistically and that has made all the difference.

The current effort by the Open Orthodox to make Judaism more egalitarianism, while certainly more limited that the open breaches advocated by Conservativism back in the day are no less significant and indicative of the same attitude. This generation may only be interested in ensuring women have equal learning and teaching opportunities with men but their daughters will surely wonder why the buck stops there and demand further change.

But where is the breaking point? How do we differentiate this group from normative Orthodoxy and know that it's not part of the acceptable routine? There are a couple of clues.

There is, for example, this quote from Rav Daniel Sperber:

“One of the major things halacha needs is compassion,” said Sperber, illuminating the question through the prooftexts brought by foremost halachic scholar Rabbi Moshe Feinstein. He used a section that stated that it is not halacha, rather a traditional practice that menstruating women (in medieval times) did not attend the synagogue — unless, the text continues, it causes them undue personal suffering, in which case they should attend.

“Smicha is an important event, but it’s sort of like a halfway house,” said Sperber. “You need to know the Shulhan Aruch [a codex of Jewish law] well, and then how to get over the Shulhan Aruch.”

Sperber charged the new rabbis with making sure people are not suffering, and to “push aside the next gatekeeper” and go into the next room filled with a halacha of compassionate love and peace.

Now Rav Sperber needs neither my complements nor my criticism. He is a fine talmid chacham with a well-earner authoritative reputation. Having said that, a legal expert who is advocating a significant change in the law and resorts not to precedent, wording or textual analysis but rather to love and peace is one that doesn't have much of a case. The phrase "get over the Shulchan Aruch" is also a red flag. Yes, the greatest poskim in the world might have that kind of flexibility in their decision making, graduates of a basic smichah program, male or female simply do not.

But perhaps the real money quote comes from this article in Haaretz:

“We must not be afraid of the title ‘rabbi.’ I’m impatient. I’m too old. If the Torah doesn’t move forward with the people, it will remain in the desert, and that will be a disaster."

That one line solidifies why what these programs and participants are doing, despite their sincerity and protests to the contrary, is not Orthodox. Note that the first two statements start with the first person singular: I. I want this. Not 'this is important' or 'this is necessary' but rather it's all about me. And what's the follow up sentence? The Torah, if it does not accommodate her, becomes irrelevant. This position isn't Orthodoxy, it's anti-Orthodoxy. Someone who feels the Torah has to change to remain relevant and guiding is Orthoprax and needs to be called on it.

Given its obsession with egalitarianism the movement needs a new name: Feminine Orthopraxy, FO, sounds right to me. What do ya'll think?

Friday, 12 June 2015

Another Migration Needed

It's no secret that small town Judaism is withering across North America. From one coast to the other large communities are managing to maintain themselves or even grow but the small ones are diminishing and disappearing. This stands in stark contrast to the situation in the early and mid twentieth centuries when small thriving Jewish communities dotted the landscape of Canada and the US and the history of Eastern Europe and its long-lived shetl society. What's changed to cause this to occur?

Right now I'm reading through a history of the Jewish community I come from. That community was always small, maxing out at around 700 families through the 1970's to 2000 but now down to somewhere around 500. What made it thrive? Why is it slowly falling apart?

I would venture the following reasons come into play here:

1) Migration - most small Jewish communities in North America started off slowly, isolated small groups settling in growing villages. All this changed after waves of immigration from Europe occurred, initially after the Czarist pogroms in the waning days of the Russian Empire, then the post-World War I refugees and finally survivors of the Holocaust. In each case a number of immigrants decided the big cities weren't for them and moved to smaller peripheral towns looking for work and opportunities or to join family already living there.

Today there are no migrations going on. The last large one was the Russian exodus in the 1990's and there is no large Jewish community in the world right now, with the possible exception of France, looking to move en masse. Even if the French do make the right decision and flee Croissant Country they will likely either go to Israel or Montreal, not scatter themselves around North America. Thus any small communities hoping to grow from the run-off from nearby metropolitan ones are likely to be frustrated.

2) Retention - life in a smaller centre isn't easy for lots of Jewish folks. For the frum there's a sense of isolation from the larger community. There are less services, less shiurim, less options for davening and less perceived opportunity for personal growth. Even those frum families that build a life in small communities tend to see their children move away after the year in Israel or university as those kids seek to make their own lives and want contact with a larger group of people than they grew up with. What's more, where the children go the parents often follow.

3) Opportunity - as mentioned in (1) lots of arrivals in small Jewish communities in the early and mid-twentieth century chose the location because the big cities were already full of immigrants competing for a limited number of low-level jobs like peddling and scrap dealing. Today small towns often provide less employment opportunities than large cities because of the concentration of growing industries in metropolitan areas.

4) Education - once upon a time a cheder was enough of an educational institution for a small Jewish community. Most people weren't frum and were more than satisfied with their children learning to read Hebrew and a couple of tunes for Adon Olam. Nowadays those who choose Jewish education with a serious intention of teaching their kids something of our national heritage choose day schools and those things are bloody expensive to run. It's a small wonder that any small communities, including the one I live in, manage to maintain a elementary level school. We have no hope of anything secondary, even a mixed community model. Parents who don't want their children moving out for grade 9 don't want to live in such a place.

For these four reasons there is little hope of reversing the ongoing trend of declining small town populations. But what are the advantages of living in a small community?

In my humble opinion I think it's time for another migration but now it should be an internal one. It's time for the frum populations of large cities to consider heading out to the boondocks. Why?

1) Cost of living - Jewish communities in large population centres are faced with huge costs. Housing is expensive. Schooling is expensive. Property taxes are expensive. Food is expensive. The smaller towns some distance from these areas offer many advantages here. Housing is more reasonable. Schooling is a little more reasonable. Property taxes aren't quite as high. Food is still expensive but a lack of restaurants means one eats out less so that'll cut the total somewhat. People struggling with unsustainable mortgages or big city tuitions might want to consider how fiscally relieving life in the smaller city might be.

2) Educational opportunity - yes, I wrote that there is much less choice in a small town but the flip side is that, since the local community school is desperate for any tuition-paying family it can dredge up, the frum family finds itself in an unaccustomed position. In the big city yeshivos and other institutions generally dictate to the families. You want your child to get a Jewish education? You have to follow their rules even when those rules dictate how to live in your own home. In the small town it's quite often the opposite. The school is often more than willing to bend over backwards to accommodate a family with a large number of children and if there's a chance for additional donations, so much the better. Letters from the school like "If you show up to get your kids make sure you're wearing a full sheitl and head to toe robing" are replaced with "Show up naked to get your kids for all we care, just send us kids!" Imagine the power that comes with that.

3) Social pressure - surrounded by a non-religious majority the environment where other frum folks judge you based on their preconceived notions of how you should act disappears. You don't have to keep up with the Jonesteins in a small town and that can be liberating for many. Imagine living the frum life because you want to, not because you don't want to be cast out from the neighbourhood social circle. What's more, in a small community everyone matters. The same person who is a cipher in the crowd in the big city is a meaningful contributor whose presence is noted in the little community.

In summary, despite the disadvantages there are many good reasons a frum family, struggling to keep up with the bills and chafing under endless social pressure would do well to consider migrating to a small town. It might be the start of a positive frum life for many.

Right now I'm reading through a history of the Jewish community I come from. That community was always small, maxing out at around 700 families through the 1970's to 2000 but now down to somewhere around 500. What made it thrive? Why is it slowly falling apart?

I would venture the following reasons come into play here:

1) Migration - most small Jewish communities in North America started off slowly, isolated small groups settling in growing villages. All this changed after waves of immigration from Europe occurred, initially after the Czarist pogroms in the waning days of the Russian Empire, then the post-World War I refugees and finally survivors of the Holocaust. In each case a number of immigrants decided the big cities weren't for them and moved to smaller peripheral towns looking for work and opportunities or to join family already living there.

Today there are no migrations going on. The last large one was the Russian exodus in the 1990's and there is no large Jewish community in the world right now, with the possible exception of France, looking to move en masse. Even if the French do make the right decision and flee Croissant Country they will likely either go to Israel or Montreal, not scatter themselves around North America. Thus any small communities hoping to grow from the run-off from nearby metropolitan ones are likely to be frustrated.

2) Retention - life in a smaller centre isn't easy for lots of Jewish folks. For the frum there's a sense of isolation from the larger community. There are less services, less shiurim, less options for davening and less perceived opportunity for personal growth. Even those frum families that build a life in small communities tend to see their children move away after the year in Israel or university as those kids seek to make their own lives and want contact with a larger group of people than they grew up with. What's more, where the children go the parents often follow.

3) Opportunity - as mentioned in (1) lots of arrivals in small Jewish communities in the early and mid-twentieth century chose the location because the big cities were already full of immigrants competing for a limited number of low-level jobs like peddling and scrap dealing. Today small towns often provide less employment opportunities than large cities because of the concentration of growing industries in metropolitan areas.

4) Education - once upon a time a cheder was enough of an educational institution for a small Jewish community. Most people weren't frum and were more than satisfied with their children learning to read Hebrew and a couple of tunes for Adon Olam. Nowadays those who choose Jewish education with a serious intention of teaching their kids something of our national heritage choose day schools and those things are bloody expensive to run. It's a small wonder that any small communities, including the one I live in, manage to maintain a elementary level school. We have no hope of anything secondary, even a mixed community model. Parents who don't want their children moving out for grade 9 don't want to live in such a place.

For these four reasons there is little hope of reversing the ongoing trend of declining small town populations. But what are the advantages of living in a small community?

In my humble opinion I think it's time for another migration but now it should be an internal one. It's time for the frum populations of large cities to consider heading out to the boondocks. Why?

1) Cost of living - Jewish communities in large population centres are faced with huge costs. Housing is expensive. Schooling is expensive. Property taxes are expensive. Food is expensive. The smaller towns some distance from these areas offer many advantages here. Housing is more reasonable. Schooling is a little more reasonable. Property taxes aren't quite as high. Food is still expensive but a lack of restaurants means one eats out less so that'll cut the total somewhat. People struggling with unsustainable mortgages or big city tuitions might want to consider how fiscally relieving life in the smaller city might be.

2) Educational opportunity - yes, I wrote that there is much less choice in a small town but the flip side is that, since the local community school is desperate for any tuition-paying family it can dredge up, the frum family finds itself in an unaccustomed position. In the big city yeshivos and other institutions generally dictate to the families. You want your child to get a Jewish education? You have to follow their rules even when those rules dictate how to live in your own home. In the small town it's quite often the opposite. The school is often more than willing to bend over backwards to accommodate a family with a large number of children and if there's a chance for additional donations, so much the better. Letters from the school like "If you show up to get your kids make sure you're wearing a full sheitl and head to toe robing" are replaced with "Show up naked to get your kids for all we care, just send us kids!" Imagine the power that comes with that.

3) Social pressure - surrounded by a non-religious majority the environment where other frum folks judge you based on their preconceived notions of how you should act disappears. You don't have to keep up with the Jonesteins in a small town and that can be liberating for many. Imagine living the frum life because you want to, not because you don't want to be cast out from the neighbourhood social circle. What's more, in a small community everyone matters. The same person who is a cipher in the crowd in the big city is a meaningful contributor whose presence is noted in the little community.

In summary, despite the disadvantages there are many good reasons a frum family, struggling to keep up with the bills and chafing under endless social pressure would do well to consider migrating to a small town. It might be the start of a positive frum life for many.

Wednesday, 10 June 2015

The True Palestinian State

Once upon a time Salim Mansur, a poli sci professor at the University of Western Ontario (go 'Stangs!), was a virulent critic of Israel, indistinguishable from the rabid Jew-haters that daily fill their air waves and media, both electronic and print, with their venom. Somewhere along the line he had an epiphany and came to realize that Israel is not the evil entity he thought it was and began to write positive things about it. Despite a strong backlash from his community and former "friends" he has continued to be a passionate advocate for peace in the Middle East along with supporting Israel. His latest piece, written together with Geoffrey Clarfield, deserves to be widely read because it destroys one of the enduring myths that Jew haters around the world thrive on.

The thesis is quite simple and is uncontested history. During the First World War Britain promised both the Jewish community of Israel as well as lots of local Arab tribes that it would assist their efforts towards self-determination if those groups aided British efforts againt the Ottoman Empire. The Jews and Arab tribes complied and only later discovered that the British had promised the same patch of land to different groups. As the conventional history goes, Israel was promised to both the Israelis and the so-called Palestinians, setting up this endless conflict that serves only to cause death, misery and keep Tzipi Livni busy travelling around.

But the truth is quite different. Yes, Britain promised Israel to both Jews and Arabs but what we are never reminded of is that Israel, or more specifically Mandatory Palestine, consisted of both what is Israel today (including Yesha) and the Kingdom of Jordan. What's more, the Mandate was conferred officially by the League of Nations which meant that the building of a Jewish homeland on that land was the exclusive objective the British were supposed to be assisting.

Instead, as is well know, the British decided that their political needs outweighed their sense of honour. In order to reward the Hashemi tribe of Hejaz (the western part of the Arabian penninsula) who were getting whupped by the Saudi tribe in a regional war they moved their allies up to Jordan, drew a border down the river and Aravah and created the kingdom of Transjordan (now Jordan). What's more, in addition to betraying the terms of the Mandate they made sure the new kingdom would be Judenrein even as they encouraging the flooding of what was left of "Palestine by Arabs and North Africans from across the Middle East in order to swamp the Jewish population and create a demographic situation in which they could credibly claim that there was no further point in encouraging the building of a Jewish state.

Mansur and Clarfield summarize this history admirably and then point out the blindingly obvious: Jordan is the real Palestine. Demographically it's 75% or more so-called Palestinian. The queen is a so-called Palestinian as well as the royal progeny. Meanwhile the Hashemis are a distinct and foreign minority holding power only because, despite a rubber stamp parliament, Jordan remains a dictatorial monarchy.

As the authors point out:

The thesis is quite simple and is uncontested history. During the First World War Britain promised both the Jewish community of Israel as well as lots of local Arab tribes that it would assist their efforts towards self-determination if those groups aided British efforts againt the Ottoman Empire. The Jews and Arab tribes complied and only later discovered that the British had promised the same patch of land to different groups. As the conventional history goes, Israel was promised to both the Israelis and the so-called Palestinians, setting up this endless conflict that serves only to cause death, misery and keep Tzipi Livni busy travelling around.

But the truth is quite different. Yes, Britain promised Israel to both Jews and Arabs but what we are never reminded of is that Israel, or more specifically Mandatory Palestine, consisted of both what is Israel today (including Yesha) and the Kingdom of Jordan. What's more, the Mandate was conferred officially by the League of Nations which meant that the building of a Jewish homeland on that land was the exclusive objective the British were supposed to be assisting.

Instead, as is well know, the British decided that their political needs outweighed their sense of honour. In order to reward the Hashemi tribe of Hejaz (the western part of the Arabian penninsula) who were getting whupped by the Saudi tribe in a regional war they moved their allies up to Jordan, drew a border down the river and Aravah and created the kingdom of Transjordan (now Jordan). What's more, in addition to betraying the terms of the Mandate they made sure the new kingdom would be Judenrein even as they encouraging the flooding of what was left of "Palestine by Arabs and North Africans from across the Middle East in order to swamp the Jewish population and create a demographic situation in which they could credibly claim that there was no further point in encouraging the building of a Jewish state.

Mansur and Clarfield summarize this history admirably and then point out the blindingly obvious: Jordan is the real Palestine. Demographically it's 75% or more so-called Palestinian. The queen is a so-called Palestinian as well as the royal progeny. Meanwhile the Hashemis are a distinct and foreign minority holding power only because, despite a rubber stamp parliament, Jordan remains a dictatorial monarchy.

As the authors point out:

The political and ethnographic disappearance of the Palestinian nature of the Arabs of Eastern Palestine (Jordan), has largely been a tactic used by the Arab League, and its allies on the left, to put Israel and its supporters on the defensive, for many Arabs have made public statements in favor of the Jordan-is-Palestine argument. They just happen to do so in a way that usually implies the destruction of the Jewish State.This then is the ultimate proof of the supposed "I hate Israel but I love Jews" lobby. There is a Palestinian state and it has the capacity to absorb the supposed Palestinian diaspora. So why is it that we keep hearing about how Israel is occupying Palestine when it's really next door?

For example, on Feb. 2, 1970. Prince Hassan of the Jordanian National Assembly said, “Palestine is Jordan and Jordan is Palestine: there is only one land, with one history and one and the same fate.” On March 14, 1977, Farouk Kaddumi, the head of the PLO political department told Newsweek, “There should be a kind of linkage because Jordanians and Palestinians are considered by the PLO as one people.”

Also in 1977, speaking to a Dutch newspaper, PLO representative Zouhair Muhsen said, “For tactical reasons, Jordan, which is a sovereign state with defined borders, cannot raise claims to Haifa and Jaffa, while as a Palestinian, I can undoubtedly demand Haifa, Jaffa, Beer-Sheva and Jerusalem. However, the moment we reclaim our right to all of Palestine, we will not wait even a minute to unite Palestine and Jordan.”

Perhaps the most revealing public quote by Muhsen was when he bluntly stated that “There are no differences between Jordanians, Palestinians, Syrians and Lebanese. We are all part of one nation. It is only for political reasons that we carefully underline our Palestinian identity. … The existence of a separate Palestinian identity serves only tactical purposes. The founding of a Palestinian state is a new tool in the continuing battle against Israel.” (And this goes some way to explaining why Arab states rise and fall so quickly. They have little historical or ethnographic unity, with the exception of Egypt.)

Mudar Zahran is an Arab, Muslim, Palestinian Jordanian who has had to flee Jordan because he has told the truth to his fellow Arabs — that Jordan is a Palestinian State. In a recent article he has bluntly stated: “There is, in fact, almost nothing un-Palestinian about Jordan except for the royal family. Despite decades of official imposaition of a Bedouin image on the country, and even Bedouin accents on state television, the Palestinian identity is still the most dominant … to the point where the Jordanian capital, Amman, is the largest and most populated Palestinian city anywhere. Palestinians view it as a symbol of their economic success and ability to excel. Moreover, empowering a Palestinian statehood for Jordan has a well-founded and legally accepted grounding: The minute the minimum level of democracy is applied to Jordan, the Palestinian majority would, by right, take over the political momentum.”

Monday, 8 June 2015

Book Review - New Heavens and A New Earth

One of the critical differences between Torah and science is that the former builds on a initial Revelation that set down the principles of halacha that can never be changed while the latter developed slowly through human investigation and is open to change if existing presumptions can be shown to be incorrect. The real conflict between Torah and science comes from scientists who don't understand that halacha's founding principles cannot be challenged and that all subsequent legal development must be guided by them, and by Torah scholars who think that science's approach to destroying its own historical positions means that it has no validity.

Into this ongoing issue comes Jeremy Brown's book, New Heavens and A New Earth. The book is well-written and organized, presenting a history of the development of Copernicus' theory that we live in a heliocentric universe instead of a geocentric one.

One mistake we often make when looking back at science throughout history is to consciously or subconsciously assume that what it obvious to us was obvious to our forbears. Brown, however, does a fine job reminding us of the state of science and also brings excellent descriptions of the debates that occurred in the astronomical community when conflicts between the Ptolemaic proponents and Copernican opponents began.

For example, when describing the geocentric model he notes that it did not develop simply out of a superficial literal reading of the Bible but was investigated using the astronomical tools and methods of the time. The nafka mina was that the Copernican system, when it was first developed, had to challenge not only religious dogmatism but also had to provide sufficient proof it was correct. Brown notes in a several places that the scientific community had multiple valid objections to Copernicas' system that prevents its immediate adoption and which, using the technology of the time, were quite valid.

The main part of the book is the Jewish encounter with heliocentrism. Like the Catholics, Jewish thinkers began with the Bible and continued with the Talmud, deriving from there a geocentric view of the universe. The idea that the sun was the centre and that the Earth was circling it was heresy to them and they initially (and for a while after) rejected it vigorously.

However Jewish astronomers, many of them devoutly Torah-observant, soon began their own investigations in concert with the greatest contemporary Chrsitian astronomers and began to realize that there was something to this heliocentrism thing which only increased the level of debate within the Torah community. Brown meticulously documents the reactions and counter-reactions within our literature, proceeding from the time of Copernicus up until the present day. He examines teshuvos and science textbooks written by Torah scholars to show how heliocentrism slowly came to be accepted as an acceptable Torah viewpoint throughout the Jewish community despite aggressive opposition from traditionalist, most of whom had never looked through a telescope.

The final section of the book deals with the issue in modern times and I found this to be most fascinating. One would think that with the advent of modern telescopes and the launches of space probes over the last fifty years the debate would be settled. After all we can see the solar system and how it's set up along with its relative position in the galaxy and that galaxy's relative position in the universe. This is no longer a discussion using indirect evidence or mathematical models. Yet there are still segments in the Torah world that reject geocentrism, something I find bizarre.

The most famous examples are the Satmar and Lubavitcher rebbes, For the Satmar to reject heliocentrism should not come as a shock. He also didn't believe that astronauts really landed on the moon. His entire understanding of reality came from our holy literature independent of, and probably despite, confirmed scientific knowledge.

But the Lubavitcher Rebbe actually had a real education in his youth and was regarded as having maintain currency in scientific and engineering fields throughout his life in addition to his prodigious Torah knowledge. Despite this he is on record as rejecting heliocentrism, as brought in Brown's book, for the simple reason that a literal reading of the Bible says it can't be, therefore it isn't and all the scientists in the world are wrong. The best part of the section is where Brown brings a quote of Rebbe invoking the theory of general relatively to justify his geocentric position juxtaposed with a quote from Einstein, the developer of that theory, stating that anyone who used general relativity to justify a geocentric universe didn't really understand it!

At the very end Brown brushes up against the subject of heliocentrism vs geocentrism in the 21st century and although he only hints at it he does note the trend by modern Chareidism to react to any universal scientific understandings by rejecting them and then setting up that rejection as a ikkar enumah. This has started happening in astronomy with the Chareidi brain trust essentially creating a new principle of faith that the universe is geocentric and that disagreeing means rejecting the Torah. It's still a small group, to be sure (most Chareidim have no interest in astronomy it seems) but it seems to me that one day we might be told that, along with direct metzitzah b'peh and a 5775 year old Earth, we must also believe that this same young Earth sits at the centre of everything or risk being labelled as heretics. I have personally spoken with an educated psychologist in my community who firmly believes in a geocentric universe because a gadol in the large Jewish community next door told me he has to. In other words we are slowly moving towards a point where a certain community might announce that unless you reject tangible reality you don't believe in the Creator of that reality.

This book provides a great read but also reassurance that there is enough support in our holy literature to reject such a demand handily.

Thursday, 4 June 2015

Who's Really Messing Up The Mesorah?

Years ago, during the latter part of the Great Slifkin Controversy, a speaker at one of the annual Agudah conventions famously announced that "the Gedolim" were to be so awesomely respected that asking them any questions about their rulings and decisions was forbidden. We are so beneath their level, the speaker claimed, that we haven't the privilege or right to query them about such things. Ours is to accept their commands without thinking for ourselves.

That statement has always bothered me but for a long time I dismissed as typical of the thinking of modern day Chareidism. The main defining feature of that ideology has always been that of the individual subsuming himself and his personal identity to his community as exemplified and led by "the Gedolim".

Recently I was thinking more about this and I realized why I was so bothered by it. In his comments to the opening of the first chapter of Pirkei Avos, Rav Shimshon Rafael Hirsch, zt"l, notes that unlike other religions, Judaism believes in spreading Torah knowledge through the masses rather than keeping it as the exclusive possession of the intellectual elite. We are not mean to be blind followers but educated ones.

Thus the ideal model is one in which the decision rendered by a posek is a teachable moment. The shailoh is asked, the answer is given and the questioner must then feel free to ask for the reasons behind it. Similarly the posek should be eager to share his reasoning. What's more he should be open to challenges from the questioner since adding to the questioner's knowledge base and correcting misunderstandings is his sacred duty. The answer "Just do what I say 'cause I said it!" is anathema to that. Yet this is exactly what the speaker at the convention seemed to imply.

Now if this was an internal philosophy of Chareidism I wouldn't be so annoyed by it but as has been well documented, the Chareidi leadership both in North America and Israel seems intent on creating the public perception that the only real Orthodox Jew is a Chareidi one and that any other type of Torah observant is a second best deviation from the true form. It is elementary logic to note that if this is true then mindless obedience to Torah leadership is an essential element of Jewish practice.

Yet we know this is not true. The greatest mitzvah is the study of Torah. A person with knowledge has an obligation to share it and the more one knows the greater the obligation.

Now, I can understand why this trend is occurring. The Chareidi community is dealing with an outside world that is doing two things: first, through the internet it is making its presence felt within even the most insular communities and second, it has made the acquisition of knowledge far more accessible than at any time in history.

Think about it. Once upon a time if you wanted to learn Talmud you had to find a Rav willing to teach you and sit on a creaky wooden bench squinting at smudged letters while trying to make sense of it, all by the light of flickering candles. Now you can sit at your desk, open your Steinsaltz Talmud and learn at your own pace from an illustrated text with translation and commentary. It's the same with the previously obscure Yerushalmi, the Midrash, Kitzur Shulchan Aruch and any other number of texts. Even those books that have been to be translated like the actual Shulchan Aruch are available in new editions where the typeset is - gasp! - legible.

Whereas once upon a time the layman would go to the Rav with his shailoh and simply accept what he was told, nowadays he often goes armed with his own research. He already has an idea of what the answer is and oftentimes just wants confirmation. And if the answer is different he has sources with which to object to it and ask for clarification.

I can understand why this would be irritating to the Chareidi leadership. As a physician it grates my teeth when people come in and tell me their diagnosis and expected prescription based on what "Dr. Google" has told them. It can only be worse for poskim with years of training to have to listen to someone with a Bar Ilan CD tell them what they think.

But what's the response? There are two: the quick and wrong and the long and right. The quick and wrong is becoming the Chareidi standard: Shut up, you don't know anything, here's the answer, now go away and don't you dare question me! When a speaker at the Agudah convention stands up and says that emunas chachamim means blindly obeying "the Gedolim" that's what he's really saying. That's how a leader maintains absolute power. That's for men who want to be kings.

The alternative is the better Torah approach but it takes time. The Rav has to sit down, review the questioner's sources, his own and then justify his conclusion. He has to explain and each, expand the questioner's mind and create the situation when the person leaves with a complete understanding of the issue and why his approach was so incomplete. Most importantly it must be done in an inspirational way so that the questioner feels that not only has his shailoh been answered but that he is a better eved HaShem for having asked it. That's how teachers raise students. That's for men who want each member of knesses Yisrael to feel a connection to the Torah.

And that's what we should be striving for.

That statement has always bothered me but for a long time I dismissed as typical of the thinking of modern day Chareidism. The main defining feature of that ideology has always been that of the individual subsuming himself and his personal identity to his community as exemplified and led by "the Gedolim".

Recently I was thinking more about this and I realized why I was so bothered by it. In his comments to the opening of the first chapter of Pirkei Avos, Rav Shimshon Rafael Hirsch, zt"l, notes that unlike other religions, Judaism believes in spreading Torah knowledge through the masses rather than keeping it as the exclusive possession of the intellectual elite. We are not mean to be blind followers but educated ones.

Thus the ideal model is one in which the decision rendered by a posek is a teachable moment. The shailoh is asked, the answer is given and the questioner must then feel free to ask for the reasons behind it. Similarly the posek should be eager to share his reasoning. What's more he should be open to challenges from the questioner since adding to the questioner's knowledge base and correcting misunderstandings is his sacred duty. The answer "Just do what I say 'cause I said it!" is anathema to that. Yet this is exactly what the speaker at the convention seemed to imply.

Now if this was an internal philosophy of Chareidism I wouldn't be so annoyed by it but as has been well documented, the Chareidi leadership both in North America and Israel seems intent on creating the public perception that the only real Orthodox Jew is a Chareidi one and that any other type of Torah observant is a second best deviation from the true form. It is elementary logic to note that if this is true then mindless obedience to Torah leadership is an essential element of Jewish practice.

Yet we know this is not true. The greatest mitzvah is the study of Torah. A person with knowledge has an obligation to share it and the more one knows the greater the obligation.

Now, I can understand why this trend is occurring. The Chareidi community is dealing with an outside world that is doing two things: first, through the internet it is making its presence felt within even the most insular communities and second, it has made the acquisition of knowledge far more accessible than at any time in history.

Think about it. Once upon a time if you wanted to learn Talmud you had to find a Rav willing to teach you and sit on a creaky wooden bench squinting at smudged letters while trying to make sense of it, all by the light of flickering candles. Now you can sit at your desk, open your Steinsaltz Talmud and learn at your own pace from an illustrated text with translation and commentary. It's the same with the previously obscure Yerushalmi, the Midrash, Kitzur Shulchan Aruch and any other number of texts. Even those books that have been to be translated like the actual Shulchan Aruch are available in new editions where the typeset is - gasp! - legible.

Whereas once upon a time the layman would go to the Rav with his shailoh and simply accept what he was told, nowadays he often goes armed with his own research. He already has an idea of what the answer is and oftentimes just wants confirmation. And if the answer is different he has sources with which to object to it and ask for clarification.

I can understand why this would be irritating to the Chareidi leadership. As a physician it grates my teeth when people come in and tell me their diagnosis and expected prescription based on what "Dr. Google" has told them. It can only be worse for poskim with years of training to have to listen to someone with a Bar Ilan CD tell them what they think.

But what's the response? There are two: the quick and wrong and the long and right. The quick and wrong is becoming the Chareidi standard: Shut up, you don't know anything, here's the answer, now go away and don't you dare question me! When a speaker at the Agudah convention stands up and says that emunas chachamim means blindly obeying "the Gedolim" that's what he's really saying. That's how a leader maintains absolute power. That's for men who want to be kings.

The alternative is the better Torah approach but it takes time. The Rav has to sit down, review the questioner's sources, his own and then justify his conclusion. He has to explain and each, expand the questioner's mind and create the situation when the person leaves with a complete understanding of the issue and why his approach was so incomplete. Most importantly it must be done in an inspirational way so that the questioner feels that not only has his shailoh been answered but that he is a better eved HaShem for having asked it. That's how teachers raise students. That's for men who want each member of knesses Yisrael to feel a connection to the Torah.

And that's what we should be striving for.

Tuesday, 2 June 2015

The Club We Don't Need To Be In

As a Religious Zionist I have always looked at Israeli sports with a mixed view. On one hand there is the instinctive pride one feels in seeing Jewish athletes competing with and (sometimes) holding their own against the best of other nations. On the other hand I always remember that what we as a nation need to strive for is not to be as good as the Gentiles at their own games but to emulate the holiness of the Creator in our daily lives through our observance of the mitzvos.

So it was with mixed feelings that I followed the recent crisis in Israeli sports, the one caused by the Arabs attempting to have Israel's national team kicked out of FIFA.

To be fair I'm not sure what the overall impact of such a move would have been on Israel. It's not like the Israeli team ever makes it anywhere near the World Cup and an expulsion wouldn't affect the thriving national league. There would certainly be a blow to the country's sporting pride but are we still so insecure that we need the Gentile world's approval to feel good about ourselves?

Fortunately or not the motion was recently withdrawn. This was no doubt a tactical move by the Arabs. Perhaps they knew that the Israelis had enough supportive votes to cause the motion to fail and, instead of being humiliated in from of FIFA our enemies chose to be "magnanimous" and cease their efforts.

I think it's more likely that the recent scandal regarding corruption at the highest levels of FIFA (although not the president himself, oh no, not him!) was the guiding factor behind the withdrawal.

FIFA doesn't look terribly good in the eyes of the world right now. Most people knew that, like the IOC, the executive of the organization is hopelessly corrupt. They know that the 2022 Qatar World Cup effort is supported by slave labour and that Third World workers are dying on a daily basis to build the sheikhdom's stadiums. They know decisions are made based on bribery and graft. Even so, this scandal blows open any pretense FIFA's executive had about presenting themselves as even halfway decent guardians of "the beautiful game".

Imagine the response to a vote to expel Israel from FIFA at this time. They're standing in judgement of us? Crooks and thieves are deciding whether or not Israel is morally pure enough to remain in the club?

A club like that is not one that any decent person, especially a Jewish one, should be desperate to be a member of. FIFA benefits by having the Israelis there and perhaps there was pressure on the Arabs to end their expulsion efforts because of that.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)